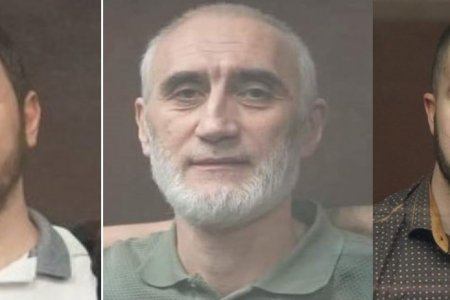

A Russian court has rejected the appeal against one of the worst sentences to date against Crimean Tatar political prisoners. The 19-year sentence passed without any recognizable crime against 35-year-old Ismet Ibragimov is in stark contrast to sentences passed for murder or other serious crimes, and comes at a time when Moscow is freeing and pardoning even multiple killers if they agree to kill Ukrainians.

On 2 October 2023, the Military court of Appeal in Vlasikha (Moscow region) under presiding ‘judge’ Igor Nikolaevich Beldzeiko upheld the earlier sentence. This ordered that Ibragimov be imprisoned for 19 years in a harsh-regime prison colony, with the first five years to be spent in a prison, the absolute worst of all Russian penal institutions. All of this means that Russia will again be violating international law and a direct judgement passed by the European Court of Human Rights (when Russia was still a member), and imprisoning Ibragimov thousands of kilometres from his home and family.

In his address to the court (in Russian this is literally his “last word’), Ibragimov stressed that this was not his final word, and that no sentence would stop him from speaking the truth. He added that those who believed that such persecution would break his people were profoundly mistaken. It had, in fact, united them, with others asking questions to which there are no answers, like why people end up persecuted for attending court trials in similar prosecutions.

Ibragimov is a scholar of Islam, and clearly views the persecution as directed against Muslims. While that may well be part of the story, in occupied Crimea, Russia has increasingly used flawed and totally unsubstantiated charges of involvement in the peaceful Hizb ut-Tahrir organization, which is legal in Ukraine, as a weapon to crush the Crimean Tatar human rights movement. At least half of the over 100 Crimean Muslims now imprisoned were civic journalists or activists from the Crimean Solidarity initiative, with many harassed and subjected to administrative prosecution. When they refused to be silenced, the FSB came for them, as Ibragimov says, bringing the same charges as those against the political prisoners whose ‘trials’ they had attended.

Ibragimov’s lawyer Emil Kurbedinov has consistently pointed to the glaring flaws in the indictment itself and the huge number of infringements at the core of the prosecution. These pertain both to the methods of falsifying ‘evidence’ and to the fact that Russia is in violation of international law by applying its legislation on occupied territory and by imprisoning Ukrainian citizens in Russia.

The charges under ‘terrorism’ legislation enable Russia to apply horrifically long sentences, without the FSB and prosecutors having to even try to prove an actual crime. The FSB claim ‘involvement’ in Hizb ut-Tahrir, and point to a highly secretive ruling by Russia’s supreme court in 2003 which declared this organization ‘terrorist’ without providing any reason. At the time, no other country considered Hizb ut-Tahrir terrorist, and the only country which, since 2016, has followed suit is Uzbekistan, which has long been criticized for its religious persecution of Hizb ut-Tahrir.

Both serious charges against Ibragimov - of ‘organizing a Hizb ut-Tahrir group’ (Article 205.5 § 1 of Russia’s criminal code) and of “planning a violent seizure of power and change in Russia’s constitutional order” (Article 278) were based solely on that unexplained ruling.

‘Evidence’

In these cases, the prosecution only has to ‘prove’ involvement in Hizb ut-Tahrir, and then cite the 2003 supreme court ruling as ‘justification’ for a 17-20-year sentence against a person who has committed no crime.

The term ‘proof’ is also understood very loosely. Ibragimov’s family stated from the outset that the armed and masked men who ‘searched’ their home on 7 July 2020, and refused to allow lawyers to be present, had planted the ‘prohibited religious literature’ that they then claimed to have found.

The only other ‘evidence’ was provided by so-called ‘secret witnesses’ whose ‘testimony’ cannot be verified, and who invariably know ‘testimony’ parroting the indictment virtually verbatim, while being unable to answer the simplest question confirming that they actually know the defendant. The court not only allows such anonymous witnesses, without there being any evidence that the person would be in danger if identified, but also blocks questions demonstrating that they are lying.

Unlike these unnamed individuals, Ibragimov’s neighbours were happy to appear openly as witnesses for the defence and reject all the allegations against him, saying they bordered on sheer fantasy.

On 8 July 2022, presiding judge Denis Galkin, together with Viacheslav Korsakov and Vladimir Tsybulnik from the Southern District Military Court in Rostov ignored all of the above, as well as the fact that Ibragimov, a father of three small children, is a recognized political prisoner. They sentenced him to the above-mentioned 19 years, with the first five of these in a prison, and to a further two years of severely restricted liberty. The sentence differed only slightly from that demanded by prosecutor Sergei Aidinov. That sentence has now, tragically, come into force.

Kurbedinov says that he will be lodging a cassation appeal, before turning to international courts on Ibragimov’s behalf.