Comparing Stalin to Hitler could soon get you prosecuted in Russia, saying they both invaded Poland already has

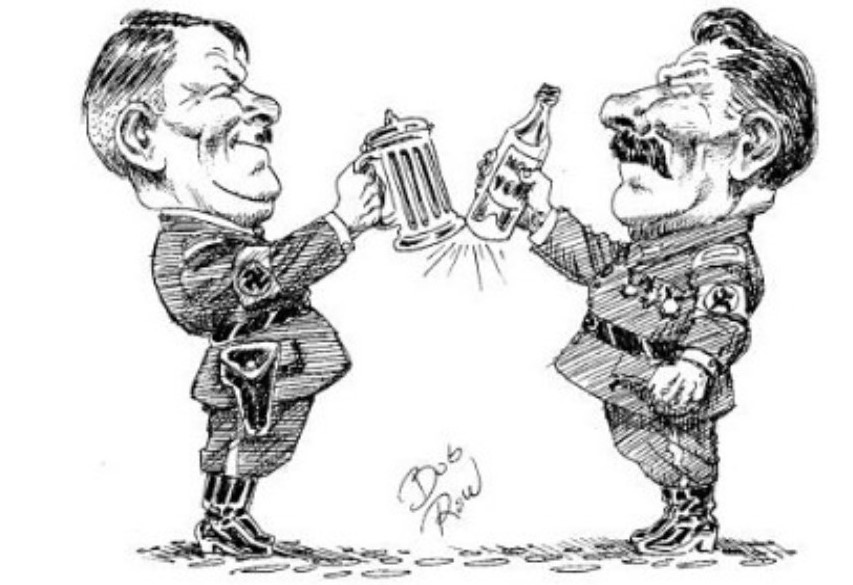

Prominent Russian legislators have tabled a bill which would ban any public statements likening the roles played by the USSR and Nazi Germany in World War II. The bill has every chance of passing into law by the 82nd anniversary of the secret agreement between Hitler and Stalin that resulted in the invasion and carving up between Germany and the USSR of what was then Poland. The Soviet Union’s active collaboration with Nazi Germany only ended when the latter invaded.

The draft bill registered on 5 May would also prohibit “the denial of the decisive role of the Soviet people in the defeat of Nazi Germany and the humanitarian mission of the USSR in liberating the countries of Europe”. Its authors are the head of the State Duma committee on culture Yelena Yampolskaya; the First Deputy Speaker of the Duma Alexander Zhukov and senator Alexei Pushkov. All are from the ruling ‘United Russia’ party, and the bill has, apparently, been drawn up in compliance with instructions from Russian President Vladimir Putin as the result of a meeting of the President’s Committee on Culture and Art on 27 October 2020.

Russia’s Investigative Committee has already expressed its support for the ban. Its official spokesperson Svetlana Petrenko stated that “attempts to re-write history must receive a warranted response in the legal realm, just like any other actions which denigrate the symbols of military glory and insult the memory of the victorious nation. The proposed additions to the law should become another effective and timely way of protecting historical memory and the conclusions of the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg. <> In conditions of a continuing information war, efforts are seen to rehabilitate Nazism both within our country and abroad, false assessments of the role of our country in the victory over fascism”.

Petrenko added that in September 2020 the Investigative Committee had created a department “for investigating crimes linked with the rehabilitation of Nazism and falsification of history”.

The words may appear unobjectionable. They are not, as a brief glance at how Russia’s Law against the Rehabilitation of Nazism has been applied since its adoption in 2014 can show In June 2016, a 37-year-old from Perm, Vladimir Luzgin, was convicted of circulating ‘knowingly false information’ and fined a very steep 200 thousand roubles for reposting an article on his social network page entitled ‘15 facts about Bandera supporters, or what the Kremlin is silent about’. It was specifically the following statement that prompted the criminal charges:

“The communists and Germany jointly invaded Poland, sparking off the Second World War. That is, communism and Nazism closely collaborated…”

This is indisputably correct, however the first instance court found it to be ‘false information’ because it contradicted the facts set out in the Nuremberg Tribunal sentences. That verdict was upheld by Russia’s Supreme Court on September 1, 2016, the 77th anniversary of Nazi Germany’s s invasion of Poland, 17 days before the anniversary of the Soviet invasion from the east. It is now awaiting examination by the European Court of Human Rights.

The scope of the new norm to be added to the law ‘On immortalizing the Victory of the Soviet people in the Great Patriotic War 1941-1945’ is so alarmingly broad that it could outlaw the works of countless historians, as well as many works of literature. While in the main these are likely to have been written by representatives of those countries who do not consider the Soviet occupation to have been ‘liberation’, they include at very least one great Russian novel (Life and Fate by Vasily Grossman). The norm would outlaw public statements, works in the public domain, material in the media and the Internet “likening the goals, decisions and actions of the Soviet leadership; command and soldiers with the goals, decisions and actions of the Nazi leadership, the command and soldiers of Nazi Germany and Axis states <> as well as the denial of the decisive role of the Soviet people in the defeat of Nazi Germany and the humanitarian mission of the USSR in liberating the countries of Europe”.

There are very many who would agree with the authors that it is unacceptable to equate the actions “of defenders of the Motherland, those who laid down their lives in the struggle for freedom and independence, the actions of liberators, with the actions directed at the extermination of peoples of the occupiers, people recognized as guilty of committing crimes by the Nuremberg Tribunal”. All of Soviet Ukraine, Belarus and large parts of the rest of the Soviet Union were occupied by the Nazis who committed the most horrific atrocities and crimes against humanity. It was the Nazis who systematically murdered men, women and children as part of their monstrous ‘Final Solution’.

The problem is, however, that the authors’ claim, in their explanatory note, that they wish to retain space for historical research and discussion, including of specific actions and specific individuals, is difficult to take seriously. The fact that the Nuremberg Tribunal, where the Soviet Union wielded considerable control, did not mention the USSR’s invasion of Poland in September 1939 was used by the highest court in Russia to justify the conviction of Luzgin for reposting material that spelled out the historically indisputable Soviet-Nazi collaboration. Given that conviction, why would historians and any ordinary person, including in Russian-occupied Crimea, believe it safe to write about equally indisputable facts, such as the murder by the Soviet NKVD of 22 thousand Polish officers and others in 1940, or the horrific rapes and killings committed by many, though of course not all, Soviet soldiers in liberated Germany. While Crimea remains under Russian occupation, the law will make it even harder to publicly speak or write about Stalin’s act of genocide in deporting the entire Crimean Tatar people.

The law will have a chilling effect on anybody planning to research or write about the above crimes; about the military blunders and bloody crimes committed by Stalin; the atrocities perpetrated by the NKVD in Western Ukraine (which had been under Poland) and the Baltic states and the deportation of entire ethnic groups.

No number of repressive laws can change facts that have been established and written about for many decades. They can however, and are certainly intended to, change which facts young people grow up believing to be true and stifle any real discussion and research in Russia and occupied Crimea. It is no accident that during the last decade, the attitude in Russia to Joseph Stalin has become frighteningly positive. With the above and other legislative initiatives in recent months and the defence ministry’s blocking of almost all access to Russian military archives from the period of the Second World War, full rehabilitation of a monster responsible for the deaths of millions seems guaranteed.