Ukraine’s Commissioner for Human Rights, Liudmyla Denisova reported on 9 May that almost 1.2 million Ukrainians have been taken to the Russian Federation, with this figure including 200 thousand children. While the Russians claim that they are ‘evacuating’ people, many are believed to have been taken against their will or through deceit, and often transported to the most inhospitable parts of the Russian Federation.

In her press briefing, Denisova spoke of the methods of so-called ‘filtration’ used by the Russian invading forces. As reported earlier, these include forcing people to take off their clothes to check tattoos for ‘suspicious’ pro-Ukrainian content and scrutinizing contacts and content of mobile telephones. All are automatically asked about their opinion of the so-called ‘special military operation’, as Russia describes its total invasion of Ukraine.

Those who ‘fail’ such filtration, being considered ‘suspect’ by the Russia’s FSB [security service] for their pro-Ukrainian views, contacts, etc., are sent to Donetsk or Dokuchaevsk on the territory of the Russian proxy ‘Donetsk people’s republic’ [DPR]. While Denisova says that no exact figures are known, she does speak of some 20 thousand people held in various camps.

Since that press briefing, more details have emerged regarding where people from Mariupol viewed as ideologically ‘unreliable’ get sent.

Petro Andriushchenko, Advisor to the Mayor of Mariupol, earlier provided details and video footage of two ‘filtration camps’ in the villages of Bezimenne and Kozatske (both in ‘DPR’]. He explained that around two thousand men from the districts of Huhlino, Myrny and Volonterivka, had been held against their will in appalling conditions for over a month.

On 11 May, Andriushchenko announced that they had received answers to many questions regarding the Mariupol residents who had ‘not passed’ the filtration procedure and had disappeared.

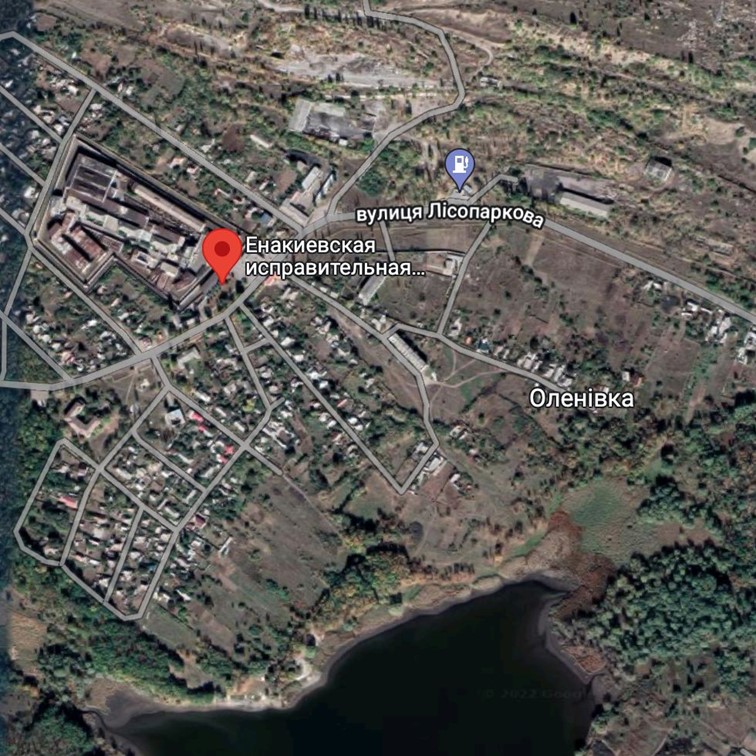

Those considered ‘unreliable’, he said, are sent to former corrective prison colony No. 52 in Olenivka (within ‘DPR’] or, possibly, to the Izolyatsia secret prison in Donetsk. No. 52 is where they place the relatives of military servicemen; former members of the law enforcement bodies; civic activists; journalists, as well as anybody deemed ‘suspicious’, for example, because of patriotic tattoos. The minimum term of incarceration is 36 days, with this the term allocated for so-called ‘filtration’. The premises are overcrowded, with facilities designed for 850 people holding at least three thousand, with most of these from Mariupol and the surrounding area. Those held there are not provided with sufficient water or food, and they are only taken to the toilet once a day. All of this is while they are subjected to interrogation lasting many hours; torture; threats of execution and attempts to force them to collaborate. Some are lucky and get released after 36 days, having been forced to sign whatever papers are thrust in front of them. Andriushchenko’s sources cannot say what the papers are, but assume that these are about collaboration. He notes that there are a huge number of cases where people simply disappear after interrogation, with the gossip being that those ones have been sent to even worse prisons, including Izolyatsia. The latter is the most notorious of the secret prisons in occupied Donbas. Former inmates call this a concentration camp and have given harrowing accounts of the torture inflicted on both men and women. In fact, Andriushchenko is almost certainly right in saying that the so-called filtration camp at Olenivka can also be called a 21st century concentration camp.

Denisova explained that it is usually the elderly, women and children who get through the initial ‘filtration’ and get sent to different parts of the Russian Federation. Denisova added that she has evidence that this enforced deportation was planned by the Russian authorities in advance, with a directive having been sent to different federal districts.

In fact, immediately prior to the total invasion, Russia and its Donbas proxies did announce total ‘evacuation’ to Russia of all women, children and the elderly from the so-called ‘Donetsk and Luhansk people’s republics’. Although there were reported to be very few takers at first, that may have changed after Russian bombs became falling throughout Ukraine.

In areas that the Russians invaded in 2022, the situation is quite different. There is considerable evidence that people were rounded up (as Denisova says, even from basements where they were hiding from the bombs) and taken away by buses. Even if some agreed to go, this would likely have been seen as the only way of surviving given Russia’s siege of Mariupol and refusal to provide corridors for those wishing to evacuate to government-controlled parts of Ukraine. Denisova also pointed out that the Russians are also taking food away, including to occupied Crimea, with this clearly part of the same deliberate policy, making it next to impossible to survive unless people agree to go to Russia.

Denisova reports that an international commission is being created with the participation of the human rights ombudspersons in countries sharing borders with Russia. A few people have, in fact, already managed to return to Ukraine thanks to arrangements involving such third party countries.

On 12 April, the Mariupol city authorities posted ‘an invitation’ issued by the Russians aimed at getting Mariupol residents to settle in Siberia, Sakhalin or other places that Russia has difficulty finding people to work in. They noted that Russia first destroys a successful and warm city on the Sea of Azov, and then drives its residents to Siberia or Sakhalin to work as cheap labour. “So how does this differ from Hitler’s policy?”, the Council asked.

Various Ukrainian and western media have spoken with people who either were themselves taken to Russia effectively against their will, or with their relatives. There are strong grounds for believing that people are then tortured or threatened into taking part in videos where they blame Ukrainian soldiers for crimes, like the bombing of the maternity hospital, known to have been committed by the Russians. The UK-based Inews reported on 7 May that it had uncovered a network of 66 camps to which Russia had sent Mariupol survivors. The study, carried out by Dean Kirby, spoke of thousands of Ukrainians having “been sent to remote camps up to 5,500 miles from their homes as Vladimir Putin’s officials follow Kremlin orders to disperse them across Russia”