Neo-Nazi Russian nationalist exposes how Russia’s leaders sent them to Ukraine to kill Ukrainians

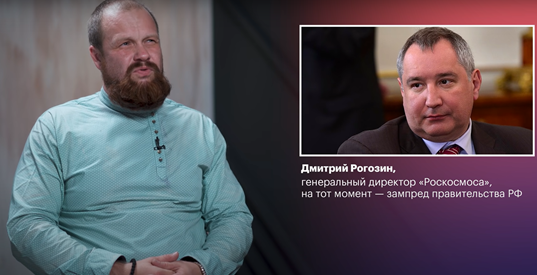

Dmitry Demushkin, a far-right Russian nationalist, has revealed details of how he was invited by the then Russian Deputy Prime Minister, Dmitry Rogozin, to gather nationalists to fight in Ukraine. Demushkin says he was initially approached by Rogozin in February 2014 and promised that he personally would be made ‘mayor’ of one of the cities in Donbas. There is no independent proof that such negotiations took place, however the machinations he describes fit very closely with those exposed by the ‘Glazyev Tapes’. These were intercepted calls between Russian President Vladimir Putin’s senior advisor Sergei Glazyev and various pro-Russian individuals in Crimea and other parts of Ukraine from 27 February to 3 March 2014. There is also evidence that other neo-Nazi and/or far-right activists were sent to Donbas. Neo-Nazi sadist Alexei Milchakov, for example, made it quite clear In a 2015 skype interview, that he, neo-Nazi comrade Yan Petrovsky and other fighters had all received money for their services. Journalist Denis Kazansky first reported (and re-broadcast)* Demushkin’s incriminating allegations made during an interview given to opposition politician and blogger Lyubov Sobol on 24 August 2021. This was not, in fact, the first time that Demushkin had spoken of the role played by Rogozin and the Russian enforcement bodies in 2014. In a May 2021 interview for Anton Krasovsky’s program ‘Antonyms’, he also linked his prosecution and imprisonment shortly afterwards with his refusal to cooperate over Donbas. The following summarizes his account in both interviews.

In May 2021, Demushkin still hesitated before naming names, but did so when prodded by Krasovsky who had asked what prompted Demushkin’s prosecutions and imprisonment. From the latter interview, it is clear that the approach from Rogozin, who was the Deputy Prime Minister with a focus on defence issues, came in February 2014. By the second interview, Demushkin was, on the contrary, indignant when Sobol asked him to confirm her understanding that “people” had come to him to get him to organize a trip of nationalists to Donbas. “Why ‘people’?’, Demushkin asks, “It was an official conversation with one of the leaders of the country at the time.” Demushkin was himself supposed to become the [self-proclaimed] ‘mayor’ of one of the major cities in Donbas, and to be in charge of gathering nationalists to fight in Donbas. “At last the Motherland calls on you to conquer, to fight for the ‘Russian World’”, he and his cronies were told.

Demushkin refused. In the interview with Sobol, he says that he does not recognize the ‘fight for a Russian World’ outside the Russian Federation and that, whenever they call on them to fight, it’s always against ‘Russians’. Unlike Vladimir Putin, who has no problem with claiming Russians and Ukrainians to be the same people, but using the first to kill the latter, Demushkin’s refusal to recognize Ukrainians as a separate people logically demands that he is not prepared ‘to kill his own’. He and his people also understood, he says, that they would simply be sent to Donbas as cannon fodder, and that, even those who were not killed, would not be able to return.

In the earlier interview, Demushkin mentions another cynical reason for why Rogozin and the FSB were so set on him and his people agreeing to go to Donbas. Demushkin’s earlier neo-Nazi ‘Slavic Union’ had been banned as extremist in 2010, but continued under the name ‘Russians’ [«Русские»] and he was also one of the organizers of the so-called ‘Russian March’. He asserts that they were the most talked about ‘nationalists’ in the media, and their very existence, the ‘Russian March’ and other headline-making nationalist events did not gel well with Moscow’s repeated attempts to present the new government in Kyiv as ‘fascist’ and Putin’s claims that “fascist, anti-Semitic hordes” had seized power in Ukraine.

In both interviews, Demushkin mentions the effective torture methods used when the FSB began trying to ‘convince’ him to be cooperative. He speaks of a whole series of prosecutions, short periods of arrest, and much latter a 2.5 year prison sentence, which did, indeed, begin with his being found guilty of organizing an extremist organization in March 2014.

A mere glance at the first months of the conflict in Donbas makes it clear that Rogozin also enlisted other far-right groups and individuals, with these having no problem with killing Ukrainians. Both the Ukrainian supporters of ‘Russian World’ ideology whom Moscow had been cultivating since 2006, and many of the Russian militants in prominent positions or involved in the fighting in Donbas had neo-Nazi or far-right views. Those involved in fighting Ukrainians in Donbas included Alexander Barkashov, head of the neo-Nazi Russian National Unity party and other members of his party; of Alexander Dugin’s ultra-nationalist Eurasia Party; Edward Limonov’s Other Russia party and Black Hundred.

The Kremlin has long cultivated close ties with far-right parties in Europe, with these providing many of the politicians whom Russia invited to ‘observe’ the farcical ‘referendums’ staged in occupied Crimea and then Donbas in the Spring of 2014, as well as the comical ‘elections’ in Donbas in November 2014.

Rogozin’s proposal that Demushkin could become a ‘mayor’ in Donbas is particularly significant for two related reasons. In early March 2014, Pavel Gubarev, a Ukrainian from Donetsk with a past in the neo-Nazi Russian National Unity party, tried to raise a ‘people’s uprising’ in Donetsk and declared himself ‘people’s mayor’. The said ‘uprising’, and the idea that there needed to be a ‘people’s mayor’, closely following the scenario pushed and lavishly financed by Putin’s advisor, Sergei Glazyev. Gubarev’s ‘uprising’ failed, and even the appearance of so-called ‘tourists’, burley Russians brought in to provide the ‘support’ they couldn’t get from local Ukrainians failed to achieve Moscow’s aim. It was only when Igor Girkin, a Russian ‘former’ FSB officer and his heavily armed and trained men arrived in Sloviansk on 12 April 2014 that parts of Donbas fell to the Russian / Russian-controlled militants.

See: Glazyev tapes debunk Russia’s lies about its annexation of Crimea and undeclared war against Ukraine

Worth noting that Gubarev has also joined an ever-increasing number of Russians or, like him, pro-Russian Ukrainian citizens, who have increasingly dropped any pretence about ‘a civil war’ in Donbas, etc. In an interview to Maxim Kalashnikov, a supporter of ‘Russian World’ ideology, Gubarev stated quite clearly that without Russian involvement, there would have been no self-proclaimed Donetsk people’s republic’, no so-called ‘Russian spring’ in Donetsk and Luhansk and that any ‘uprising’ would have died the same death that it did in Odesa and Kharkiv, Gubarev admits. It was Girkin (and his heavily armed men) who was able to “drag the uprising out of a usual, unarmed and toothless street protest”.

Girkin, in his turn, has openly admitted that the first shots and, therefore, the violence in Donbas was effectively provoked by his men.

Alexander Zhuchkovsky, who holds openly neo-Nazi Russian nationalist views, arrived in Sloviansk together with Girkin. In 2019, he published a book, entitled ’85 days in Sloviansk’ which openly speaks of Russia’s role in unleashing and carrying out military action in the east of Ukraine.

Another of the first Russian leaders of the so-called ‘Donetsk people’s republic’, far-right nationalist Alexander Borodai has also admitted that without Russia’s military intervention, he and the other ‘insurgents’ would be dead. Since he, as well as other former militants, are likely to win places in Russia’s State Duma shortly, worth noting that there are also intercepted calls which prove that he and other militant leaders were, in fact, always following orders from Moscow.

See: Russian militant who brought war to Ukraine may become MP for Putin’s United Russia party

* Denis Kazansky is providing an invaluable source of effective confessions from individuals heavily implicated in the war in Donbas. He generally reposts the most incriminating revelations, which is particularly useful, since the original interviews can often disappear, presumably because somebody has understand just how incriminating they are.