A Russian court has added 4.5 years to the five-year sentence against recognized political prisoner Oleh Prykhodko. The move is particularly ominous as identical charges could easily be laid against any of Russia’s Crimean Tatar and other Ukrainian political prisoners already serving sentences, with ‘guilty’ verdicts effectively guaranteed.

Information about the additional sentence was reported to Suspilne by Prykhodko’s daughter, Natalia Shevtsova. She explained that the court hearing had taken place on 8 November, with Prykhodko participating by video link from the notorious Vladimir Prison where he is held prisoner. They tormented him for four hours, she says, having got him there from 6 a.m. They deliberately created problems for him with speaking, constantly jumping ahead and preventing him from talking with his lawyer. Prykhodko is turning 65 in just a few days (on 21 November) and has problems with hearing which were simply ignored.

Judging by Natalia’s account, it is likely that Prykhodkho was ‘set up deliberately, with the ‘cellmates’ ensuring that he felt provoked into speaking out. Natalia confirmed what was said during the original ‘trial’, namely that her father is not restrained and does not mince words when he considers (here, with full justification) that those involved in his case are lying.

Natalia says that both she, and her father, understand that he is unlikely to come out of Russian imprisonment alive. Wherever he has been held, he has been constantly placed for up to 15 days in the punishment cell where the conditions are appalling and would strain the health of a man half Prykhodko’s age. The prison does not provide any medical care itself, and also fails to pass on the medication and parcels with food, etc. that Natalia and her mother send.

The pressure on him is enormous, with threats used both against him and against his wife and daughter, both of whom remain in occupied Crimea.

The court on 8 November sentenced Prykhodko to 9.5 years’ imprisonment, but seemingly took the earlier five-year sentence into account, with this adding four and a half years to the term of imprisonment. Only the articles of Russia’s criminal code are mentioned, however these correspond to the charges earlier reported. The court found him guilty of so-called ‘public calls to carry out terrorist activities, public justification of terrorism or propaganda of terrorism’ (Article 205.2 § 1) and of the even more dubious ‘rehabilitation of Nazism’ under Article 354.1 § 1. This article of the criminal code, which purportedly punishes those who ‘publicly deny or approve of the facts established by the Nuremberg Tribunal’, was criticized before its introduction in May 2014, and has already proven to be a weapon against historical truth. The charges were based on claims that Prykhodkho had “promoted acts of terrorism’ and “praised the actions of Hitler and his supporters during WWII”. All of this was based on the ‘testimony’ of fellow cellmates who were either deliberately placed with Prykhodko in order to bring a new prosecution, or who could be easily pressured into providing the required denunciations.

As reported, Oleh Prykhodko was one of several Ukrainians in occupied Crimea to be arrested in late 2019 after the Kremlin was forced to release 35 Ukrainian political prisoners in exchange, primarily, for Volodymyr Tsemakh, an important MH17 witness (and possibly suspect).

The almost open fabrication of the charges against him was, in fact, very reminiscent of the prosecution against one of the released political prisoners, Volodymyr Balukh, another Ukrainian who had never concealed his opposition to Russia’s invasion of Crimea.

Prykhodko was arrested in the evening of 9 October 2019 by FSB officers who made no effort to search a second garage after claiming to have ‘found’ explosives in Prykhodko’s first garage. The Ukrainian had already suffered constant harassment and administration prosecution because of his pro-Ukrainian views and had every reason to expect such FSB or occupation police ‘searches’. He also used his garages for welding and soldering and would have needed to be suicidal to store flammable substances (as claimed) near his equipment.

The initial charge was of planning to blow up the Saki City Administration building. Three months later, however, the prosecution added the even more surreal charge of having planned to set fire to the Russian general consulate building in Lviv, Western Ukraine, with the alleged ‘proof’ of this lying in a telephone and a memory stick.

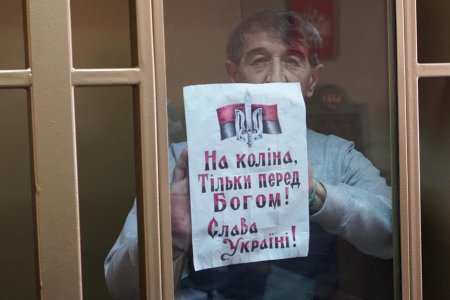

The defence provided clear evidence that the charges were falsified, however this was, typically, ignored by the panel of judges at the notorious Southern District Military Court in Rostov (Russia). On 3 March 2021, presiding ‘judge’ Alexei Abdulmazhitovich Magomadov; together with Kyrill Nikolayevich Krivtsov and Sergei Fedorovich Yarosh found Prykhodko guilty of all charges, however removed the charge under Article 223.1 (preparing explosives) as being time-barred. Prykhodko was sentenced to five years’ harsh-regime imprisonment with the first year in a prison, the worst of all Russian penal institutions. He was also fined 100 thousand roubles. As mentioned, this was significantly lower than the 11-year harsh-regime sentence demanded by Russian prosecutor Sergei Aidinov. On 17 May 2021, the sentence was upheld by the Military court of appeal in Vlasikha (Moscow region). An extra month was later added after Prykhodko was found guilty of ‘contempt of court’ over his (strongly worded!) abuse of two prosecution witnesses who stood up in court and lied about the ‘testimony’ which the defence had shown to be falsified.

The authoritative (and itself persecuted) Memorial Human Rights Centre declared Oleh Prykhodko a political prisoner back in April 2021. They found the case against the Ukrainian activist falsified and lacking in any elements of a crime. It was clear, they said, that he had been arrested and tried purely because of his political views, in particular his unwavering opposition to Russia’s occupation of his native Crimea.